Research idea

Global policy initiatives – such as Generic 21th-Century Skills (Howells, 2018) and Reimagining our Futures Together (UNESCO, 2022) – emphasise the importance of exploring tensions between educational discourses and ideas of specialised knowledge. Life in the Anthropocene can be assumed to require a renewed Bildung that transcends the ideal of human liberation and encompasses a wider notion of solidarity and responsibility (Paulsen, 2021; Sjöström & Eilks, 2020).

Exploring the Anthropocene requires an interdisciplinary and even transdisciplinary approach to Bildung (Lambert & Morgan, 2010; Taylor, 2017). Nevertheless, real-world problems also require deep knowledge and special skills that derive from specialised epistemological communities. In an educational setting.

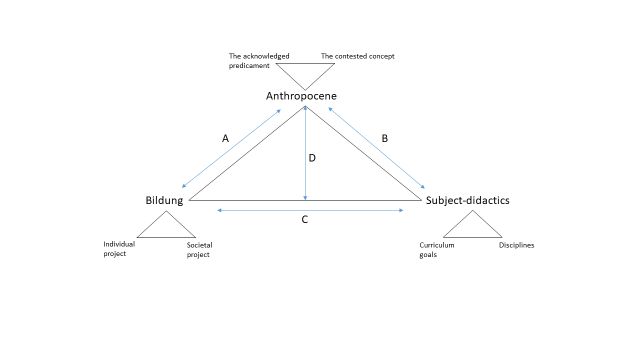

This complexity emphasises transposition’s role in selecting specialised knowledge and transforming it into school subjects (Bosch & Gascón, 2014). This logic of specialisation creates borders that determine what is accepted as valid and relevant knowledge and what is not (Bernstein, 1999). Hence, disciplinary borders both hinder and drive advancement and communication. Their language can exclude, since access requires a special inauguration (Foucault, 2020), yet also include, since its concepts and methods allow for precision and transparency (Young & Muller, 2016). Fundamentally, our network assumes that tension emerges when fields relate the Anthropocene to Bildung and subject-based education (Figure 1).

Why the Anthropocene?

The Anthropocene is a complex, controversial concept (Zalasiewicz et al., 2021). As a geological term, it not only concerns anthropogenic factors but also strongly claims that humanity is the most important geological change agent, which remains under investigation.

An ongoing discussion also concerns the extent to which it can include or obscure justice, guilt and non-human experiences (Chakrabarty, 2021; Haraway, 2015; Malm & Hornborg, 2014). We approach these problems by relating to the Anthropocene as both a theoretical conceptualisation (Lewis & Maslin, 2018) and a descriptor of the predicament facing the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere fundamental to life on Earth (Arias et al., 2021).

The Anthropocene is not only geological but also social, political, historical and cultural. Therefore, addressing lifestyle challenges and societal transformations requires an ethos shift and contemporary epistemologies and cosmologies. As Chakrabarty (2018), Latour (2021), Hornborg (2021) and Vetlesen (2020) note from different positions, the Anthropocene challenges not only the modernist framing of progress but also critical post-traditions, reintroducing universalism into history, ethics and scientific truths in relation to radical relativism. Hence, constructive ways to extend these challenges into a renewed educational system are needed. Our research problem is the renewal of a Nordic Bildung tradition and what being educated means in the Anthropocene.

Why Bildung?

The Bildung concept expresses an ideal cultivation goal, rather than a specific set of knowledge, and it is judged through the characteristics of an individual who sustains it, rather than a predefined learning outcome (Klafki, 1995; Sörlin, 2019).

While the concept can be perceived as elusive and open to widely differing values, it is distinctly rooted in Western modernity and associated with an anthropocentric worldview. Masschelein and Ricken (2003) argue that the notion should be viewed as historically situated, urging an alternative to dominant, Western life. Taylor (2017, p. 432) argues post-humanistically that a conceptualisation of education remains necessary as an ‘expressive mode of being, becoming and belonging’. She emphasises that Bildung notions have always shifted and that educated people’s agency should be reconsidered as interconnected with human culture and non-humans. The relationship between the Anthropocene, Bildung and human and non-human perspectives was also discussed recently in a Nordic context (see Torjussen & Hilt, 2021), concerning Amor Fati and Paulsen’s (2021) critique of late-Holocene educational ideals generally and, specifically, Klafki’s anthropocentric framing of key problems, as well as new ideals of education as captiousness, integrating post-human ideas.

Our approach is both retrospective and prospective. While we need education not to separate human culture from nature or human activity from planetary limits, education is never detached from its cultural heritage and the continuance of epistemic communities. Nevertheless, we are inspired by Friesen (2022), who sees Bildung as an expression of hope since humanity cannot bear mere survival but can envision an alternative future. Yet, a renewed Bildung must reverse Humboldt’s vision of human liberation as the departure from nature, championing the arrival ‘of humanity in a very direct relationship with nature’ (Friesen, 2022, p.12). This aligns with Kvamme’s (2021) argument that Bildung in the Anthropocene should also accommodate intragenerational and intergenerational justice and ecojustice, regarding the notion as a project that transcends the individual and society.

Why subject education?

The Anthropocene exposes inherent tensions in the Bildung concept, at once individual and social, and between culture and nature as ideals and independent values.

In relation to subject didactics, the Anthropocene reveals tensions between subject borders as organisational tools to investigate the world or selective traditions that repel new perspectives. But the relationship between Bildung and subject education also highlights dependencies between (a) formal education and lifelong learning and (b) authorised knowledge and knowledge as subjectification.

Based on subject-didactical research, we think education based on specialised knowledge is needed (Bernstein, 1999) as a basis for understanding humans’ complex influence on planetary systems, as well as how this influence affects politics, culture and economics. However, school subjects tend to establish selective traditions that hinder the renewal of epistemic perspectives (Englund, 2008). Hence, subject didactics must explore the dynamic tensions between the Anthropocene and specialised knowledge (Nordgren, 2021; Sund & Wickman, 2011).

From a subject-didactical perspective, we avoid generalisations that reduce school subjects to mere disciplines. The European research tradition of didaktic understands that teachers can make independent didactical decisions (Chevallard, 2007). Hence, teachers do not just transfer content, as the traditional curriculum research suggests. Consequently, understanding the Anthropocene’s implication for education requires a focus beyond curriculum principles since teachers and students alone enact curricula (Gericke et al., 2018).

Figure 1. The EBAN model:

Tensions between the Anthropocene, Bildung and subject didactics education. Arrow A: The Anthropocene problematises Bildung as a modernistic division between culture and nature but can also renew thinking beyond an anthropocentric worldview. Arrow B: Subject-based education can offer powerful knowledge with which to understand and explore the Anthropocene but also epistemic traditions that hinder such explorations. Arrow C: The relationship between Bildung and subject education exposes tensions and interdependencies between educational goals, as well as between formal and informal education. Arrow D: The Anthropocene challenges fundamental ontological and epistemological bases for education and Bildung; on the other hand, knowledge regimes frame understandings of the Anthropocene.